In a 1972 law review article, Christopher Stone proposed that we give legal rights to forests, oceans, rivers and other so-called “natural objects” in the environment-indeed, to the natural environment as a whole. Stone argued that “to say that the natural environment should have rights is not to say anything as silly as that no one should be allowed to cut down a tree.” Stone’s perspective was as follows:

Human beings have rights, but they can be restricted. Corporations have rights, but they are legal fictions; “Thus, to say that the environment should have rights is not to say that it should have every right we can imagine, or even the same body of rights as human beings have. Nor is it to say that everything in the environment should have the same rights as every other thing in the environment.

At common law “natural objects” are not holders of legal rights. Consider, for example, the common law’s posture toward the pollution of a stream. Although the courts have always been able, in some circumstances, to issue orders that will stop the pollution, “the stream itself is fundamentally rightless, with implications that deserve careful reconsideration. The first sense in which the stream is not a rights-holder has to do with standing. The stream itself has none.”

“The second sense in which the common law denies “rights” to natural objects has to do with the way in which the merits are decided in those cases in which someone is competent and willing to establish standing. At its more primitive levels, the system protected the “rights” of the property owning human with minimal weighing of any values: {(Cujus est solum) ejus est usque ad coelum et ad infernos.”

For example, continuing with the case of streams, there are commentators who speak of a “general rule” that “a riparian owner is legally entitled to have the stream flow by his land with its quality unimpaired” and observe that “an upper owner has, prima facie, no right to pollute the water.”

The rules vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, “reasonable use,” “reasonable methods of use,” “balance of convenience” or “the public interest doctrine,” but what the courts are balancing with varying degrees of directness primarily focuses on competing human interests. What does not weigh in the balance is the damage to the stream, its related ecosystem, its wildlife, its fish and turtles and “lower” life. The natural environment itself is rightless.

Stone writes that “Until the rightless thing receives its rights, we cannot see it as anything but a thing for the use of ‘us’ — those who are holding rights at the time,” he wrote. “Throughout legal history, each successive extension of rights to some new entity has been, therefore, a bit unthinkable.”

Accordingly, Stone proposed that “parts of the environment could gain legal representation using common methods, he said. If a man becomes senile and seems unable to manage his affairs, concerned parties intervene and seek the appointment of a guardian. Professor Stone suggested that groups like the Sierra Club could apply to serve as court-appointed guardians for mountains or streams that they perceive as endangered. Guardians would gain the power to sue on the environment’s behalf.”

Professor Stone referred to a case then being considered by the United States Supreme Court: Sierra Club v. Morton. The Sierra Club had sued Rogers C.B. Morton, then the secretary of the interior, to prevent the Walt Disney Company from building a resort on public land in California. In a 4-3 decision in April 1972, the justices concurred with an appeals court ruling that the Sierra Club did not have standing to sue.

However, in a famous dissent, Justice William O. Douglas adopted Professor Stone’s argument. “Contemporary public concern for protecting nature’s ecological equilibrium,” Justice Douglas wrote, “should lead to the conferral of standing upon environmental objects to sue for their own preservation.”

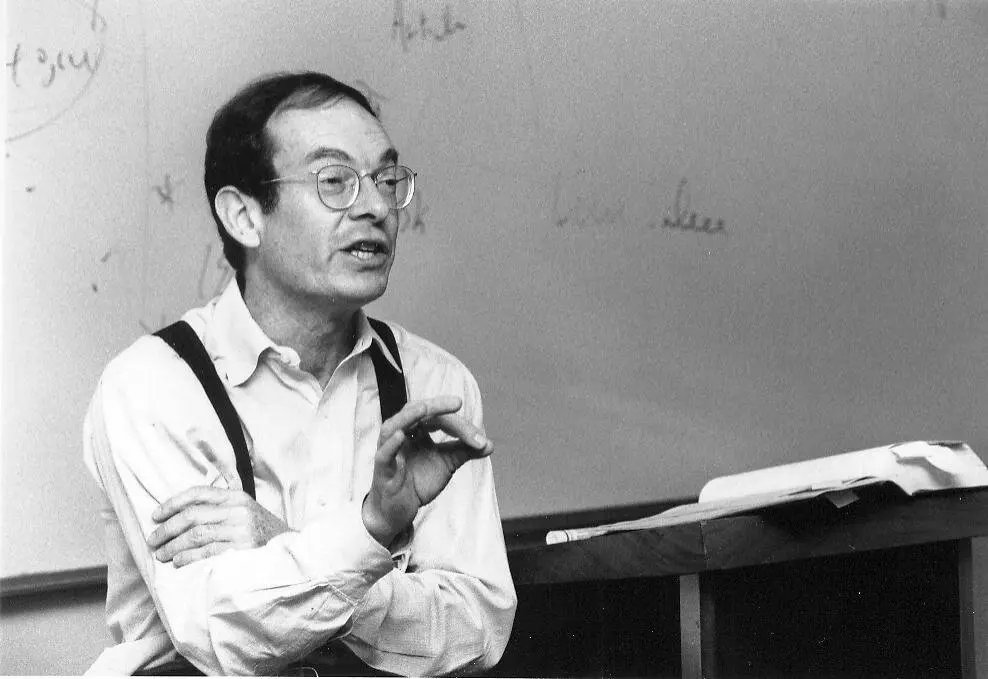

Professor Stone was the son of the crusading reporter I.F. Stone. At the time of publication of his famous article, advocating for a different legal perspective on our relationship with the law and nature, he was a 34-year-old law professor who had never published anything about the environment. In May of 2021, he passed away while at an assisted living facility in Los Angeles, California. He was 83

Check out the classic. Stone’s “Legal Rights for Trees, Should Trees Have Standing? — Toward Legal Rights for Natural Objects”, 45 S.Cal.L.Rev. 450 (1972),(pdf)